During the general election campaign, the divide between the political parties was over what kind of deal should replace the current relationship which exists under the EU Treaties between the UK and the rest of the EU. That current arrangement involves the UK being inside the EU Customs Union and participating in the EU Single Market. What then should replace that current relationship and how would it compare with the present arrangement?

The first point to make is that participation within the Single Market is a very mixed blessing. In our article Brexit and the Single Market, we explain that the rules of the European Single Market are made up of a number of different elements, some of which are helpful to trade, some of which (such as harmonised regulations) have benefits and disadvantages which counterbalance each other and may have different positive and negative impacts depending upon the sector concerned, and others of which are positively harmful and negative for the UK. In that latter category are the ‘Fortress Europe’ rules of the Single Market which positively require us to impose restrictions on trade between ourselves and non-Member States, so driving up costs to our consumers and industry.

Therefore the aim should not be to preserve participation in the European single market with its negative features. Instead, the aim should be access to the single market.

The EU trade tail should not wag the global dog

Before turning to what kind of deal with the remaining EU we should aim for, we should first ask what is the dog and what is the tail? Over the past 10 to 15 years, there has been a dramatic decline in the proportion of our trade which goes to the EU as compared with our trade which goes to the wider world.

In 1999, 55% of our exports of goods and services went to the EU. By 2015, this percentage had dropped to under 44% and it is still declining.

This speaks volumes for the supposed benefits of the Single Market – if belonging to it is really so great, why do we find it more difficult to grow our exports to the EU than to the rest of the world?

What it means, however, is that trade with the rest of the world is now more important to us than trade with the EU. This is not some passing phase but a long-term and persistent trend which seems likely to continue into the future. So, in our dealings with the EU after exit we must look first to what is best for our global trading interests outside the EU (the dog), and must ensure first and foremost that any deal regarding trade with the EU (our declining tail) does not interfere with or compromise our global trading interests.

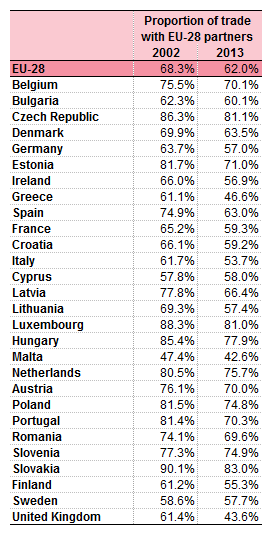

It is also worth noting how we compare with other EU Member States in our pattern of trade. The EU’s official statistics body, Eurostat, has published a comparative study of the way in which exports from different Member States go to other EU Member States or outside the EU: Intra-EU trade in goods – recent trends

That Eurostat article contains an informative table which we reproduce for the benefit of our readers:

This shows that by 2013, the percentage of our exports going to other EU states had dropped to 43.6%, the lowest percentage of any Member State except for tiny Malta. This trade pattern is hugely out of line with the rest of the EU: it is 18.4% below the EU average of 62%. It represents a major change from the position in 2002 when over 61% of our exports went to EU members, and we were much closer to the average and much more typical of the pattern of other member states.

This illustrates why the interests of the UK are so dramatically different from those of all other member states of the EU. Global trade is much more important to us than it is to other EU Member States, while exports to the rest of the EU are much less important to us than any other major EU state – the next major state closest to us in its trading pattern is Italy, which sends 53.7% of its exports to other EU states.

Since the EU club is run for the benefit of the club members who send most of their exports to each other inside the EU, it is hardly surprising that we are the club member who gets least benefit from our membership.

The EU’s best customer

The other aspect of our trading relationship with the EU is our balance of trade. We import very much more from the EU than we export to them, a trend which has persisted over recent years and appears to be growing.

According to the latest figures (2015, ONS “Pink Book”) the UK exported £134.3bn worth of goods to the r-EU but imported £223.0bn, a trade gap of -£88.7bn: we import 66% more goods from the EU than they export to us. The reason why this trade gap is important is not because it is of itself a bad thing – within a country’s overall trading pattern it will have surpluses with some trading partners and deficits with others, and there is no particular reason why one should try to achieve a trade balance with each partner.

But this trade gap does have major implications when it comes to negotiating a trade deal with the remaining EU. Any measures which inhibit trade between the UK and the r-EU after exit (such as the imposition of tariffs) would disproportionately affect EU exporters compared with UK exporters.

Rather silly comments currently are being made by certain EU politicians in an attempt to influence the outcome of the referendum claiming that terms of access to the r-EU market will be made difficult for the UK in order to deter other countries who might have the temerity to believe in democracy and be thinking of following us out of the door. Such puerile sentiments will not be reflected in reality when the jobs of German car workers and French agricultural producers are dependent upon reaching a harmonious and mutually beneficial trade deal with the UK.

Key elements of the trade deal with the EU

There is a widespread misconception that any post-Brexit trade deal with the EU would have to be based on a “model” of one of the EU’s existing external trade agreements. So it is asked whether the UK should go for a Norwegian, Swiss, Canadian or even Albanian “model”?

This is a mistaken starting point. Of course it is interesting to examine the EU’s existing trade agreements in order to see the kinds of things the EU has agreed to in the past. It is also interesting to note that the Western European countries who are outside the EU all seem to be doing very well economically and do not want to convert their existing arrangements into EU membership.

Examination of the EU’s external trade deals demonstrates that there is no fixed template and no limited “a la carte” menu from which other states must choose. The wide variety of the agreements reached simply demonstrates that the EU is willing to negotiate on a case by case basis a deal which suits the mutual interests of itself and the party it is negotiating with. Therefore it is not surprising if agreements negotiated to suit the circumstances and interests of other states with economies that differ from the UK should not be best fits for the UK’s interests.

What the UK should press for in terms of a trade-related agreement is in fact fairly straightforward and simple, and consists of three elements:

-

- A free trade agreement: A free trade agreement allowing for tariff-free entry of goods (in both directions) is a permissible departure under Article XXIV of GATT from the rule that WTO members must charge the same tariff rate to all comers. Unlike a customs union, members of a free trade area can decide on the level of the standard tariffs which they charge to non-members of the free trade area. As pointed out in our article Brexit and International Trade Treaties, this would allow the UK to charge lower or nil tariffs on goods where there is no substantial UK industry to protect, to the benefit of our consumers and industry. The r-EU would have a very strong incentive to agree to an FTA deal, in view of the huge trade imbalance pointed out above. In any case, all non-EU territories in Europe have free trade agreements with the EU apart from Belorussia.

-

- General rules on free movement of goods and services: The general rules of the EU treaties on free movement of goods and services have generally worked well and in the interests of the UK. There would be no difficulty in replicating these general rules in an EU-UK trade agreement and in fact many of the EU’s external trade agreements already do so. Since these rules are for the benefit of consumers in the state of importation, there is a strong argument for replicating these rules and applying them to goods and services imported from non-EU states as well, something which we are currently prevented by our EU membership from doing.

- Continued access for goods and services under existing regulations and directives: The EU currently has numerous regulations and directives which lay down rules with which goods and service providers must comply, in return for which the goods or services may be sold in other Member States without further regulatory restrictions. Unlike a country which might newly approach the EU for a trade relationship, the UK is currently compliant with this mass of regulations and directives. This forms the basis of a trade deal simple: so long as neither party changes the relevant rules, access will continue after exit in the same way as before. Importantly however, this would give both parties (the UK and the r-EU) the right to change the rules in a relevant area but bearing in mind that a rule change might affect the continued access rights of those businesses who export from the UK to the r-EU or vice versa.

Trade is of course not the only aspect of our current relationship with the EU where it would be sensible to continue to cooperate. A wide range of matters should be covered by inter-governmental agreements, from intelligence and security cooperation to continued participation in Europe-wide (not EU-wide) programmes such as scientific and higher education research and student exchange programmes. Such continued mutually beneficial cooperation in non-trade matters does not need to be incorporated into a trade agreement.

from: https://lawyersforbritain.org/eu-deal.shtml