Introduction: why prices will fall after Brexit, not rise

Over the past couple of weeks, the media have been full of lurid scare stories about what will happen if the UK leaves the EU on WTO terms, because negotiations with the EU do not result in a withdrawal agreement.

One of the most ridiculous and unjustified of these absurd scare stories is that it will lead to higher prices, and even shortages, of foods and medicines. In the Sunday Times on 12 August 2018, under the headline “No deal will hike food bills by 12%”, it was reported that ‘senior executives from the big four supermarkets’ had claimed that a ‘no deal’ Brexit ‘would force up the price of the average weekly food basket by as much as 12%.’

This prediction was apparently based on the suggestion that ‘the biggest tariffs on imports from the EU could include cheese, up by 44%, beef, up by 40%, and chicken, up 22%’.

This suggestion is therefore based on a misconception which is so widespread and so often repeated that I shall call it “the tariff delusion.” That delusion is that when we leave the EU, WTO rules will require the UK to take the current tariffs which the EU at present forces us to impose on imports from the rest of the world, and impose them on imports from the EU as well.

That delusion is simply not true. The UK is currently in the process of ‘rectifying’ its tariff schedules at the WTO by copy-and-pasting the EU’s current schedules. But those schedules do not specify the tariffs which we will have to charge on our imports: they specify the maximum level of tariffs which we are allowed to charge. We will be fully free to charge lower levels of tariffs, or zero tariffs, if we feel fit.

What WTO rules do require, under the so-called “Most Favoured Nation” (MFN) principle, is that whatever tariffs we decide to set must be charged equally to everyone, with the exception of countries with which we have customs union or free trade agreements. In those cases, zero tariffs must be charged on substantially all trade in goods under Article XXIV(8) of GATT.

Since we will be leaving the EU’s customs union in a “no deal” scenario without a replacement free trade agreement, we will have to charge the same UK MFN tariffs on imports from the EU as on imports from the rest of the world. But those UK MFN tariffs can be lower than the current EU-mandated tariffs or zero if we want, on some or even all categories of goods. So under a rational policy, food prices – as well as prices for other basics such as clothing, textiles, and footwear – will go down, not up. In fact, it would be an act of lunatic self-harming idiocy for any British government, even a government as stupid as the present administration, to adopt and apply the EU’s external tariffs to imports from the EU as well as on imports from the rest of the world.

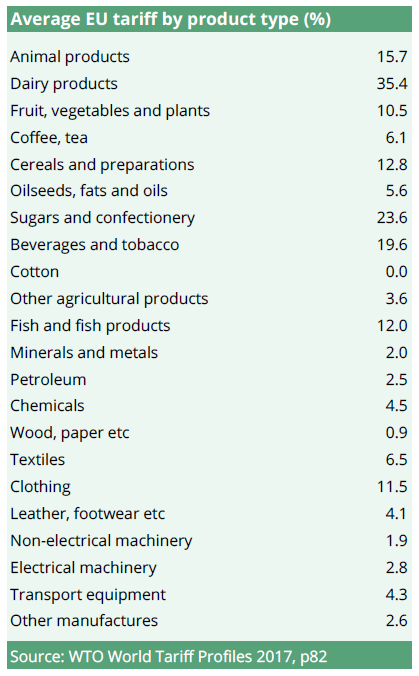

Why the EU’s external tariffs are terrible for the UK

The EU’s tariffs are terrible for the UK because the EEC’s customs union was designed and built before we joined the EEC in 1973. The tariffs were set in order to protect Continental producer interests, notably French farmers, German car makers, and Italian clothing and footwear manufacturers. Those were – and still are – the areas where the EU’s external tariffs are very high. The high food tariffs were and continue to be very damaging to us as a net food importing nation. Our consumers pay 100% of the elevated prices for food inside the EU’s tariff walls, but only part of the benefit goes to British farmers. The rest of the benefit of the higher prices goes to farmers in other EU countries.

When we applied to join the EEC in 1972, we were not in a position to make the EEC change its whole tariff policy to accommodate our consumers or our historic low food price policy which had prevailed since the repeal of the Corn Laws. Instead, part of the price of membership was to swallow the bitter pill of higher food prices. Heath’s White Paper advocating EEC entry in 1971 estimated that “membership will affect food prices gradually over a period of about six years with an increase of about 2.5 per cent each year in retail prices” (para 88 on p.23).

Although the increase was less visible because it was phased over time, this meant that the Heath government accepted on our behalf a permanent elevation of about 15% in food prices as part of the cost of entering the EEC. And this elevation of prices has persisted, with a more recent estimate that the price of food in the UK is at least 17% more expensive than it would be outside the EU (Gerard Lyons and Liam Halligan, Clean Brexit, Policy Exchange, January 2017, p10.)

And yet we have doomsayers today claiming that leaving the EU will result in food prices going up. By what mad process of logic can it be right that joining in 1973 resulted in food prices going up, and leaving in 2019 will result in food prices going up yet again to even higher levels?

We pay a subsidy of £16 billion per annum to EU27 producers because of the EU’s tariff and non-tariff barriers

The effect of the EU’s tariffs is that UK consumers pay a subsidy to producers in other EU countries. This is particularly easy to understand in the case of goods which are not made or grown in the UK. Let us take oranges as an example.

Oranges are a high tariff product: the tariff was increased to 16% in October 2016.

There is no production of oranges in the UK and therefore no domestic industry to protect. At the moment therefore the British consumer can buy Spanish oranges tariff-free, but must pay 16% tariffs on oranges imported from the rest of the world. The effect is that UK consumers have to pay 16% more for their oranges than if oranges were let into the UK at world prices, and Spanish and other EU orange growers can raise their prices to match world prices plus 16%, and pocket this extra money.

Quite apart from tariffs which increase prices inside the EU above world levels (indeed, that is the whole point of having the tariffs), the rules of the EU single market on goods also raise prices inside the EU above world levels because they create so-called “non-tariff barriers” (NTBs) against imports of many kinds of goods from outside the EU. I shall discuss some of the more important kinds of NTBs below.

It is obviously more difficult to calculate the impact of NTBs on price levels than the impact of tariffs, and one is in the hands of economists in producing numerical estimates. One estimate, by Prof Patrick Minford (Economists for Free Trade, “From Project Fear to Project Prosperity”) is that the combined effect of the EU’s tariff and non-tariff barriers on imports of goods from the rest of the world is to raise prices of food and manufactured goods inside the EU to 20% above world prices on average.

This means that UK consumers and UK companies who buy goods are paying on average 20% above world prices for goods which they buy from the EU27. It is true that by the same logic, UK exporters of goods are also reaping a 20% premium above world prices for the goods which they export to the EU27.

But – and here is the crunch point – the UK buys massively more goods from the EU27 than we export to the EU27. In 2017, we exported £164bn of goods to the EU27 and imported £259bn, giving a deficit of £95bn in goods (ONS Pink Book 2018, section 9, table 9.4).

So if the average price level of goods traded inside the EU single market is 20% above world price levels, then the net overprice paid by UK consumers and UK companies who buy goods (i.e. after offsetting the benefit to UK exporters of goods to the EU27 of receiving the overprice) is £16bn per year.

This is a staggering figure, which is paid by UK consumers to EU27 producers across the foreign exchanges on top of the world market level of prices for those goods. It is important to realise that this subsidy by the UK to the EU27 is quite separate from, and on top of, the UK’s contribution into the EU budget which is also paid across the foreign exchanges.

No doubt there is room for argument among economists about the exact level of the amount by which the EU’s NTBs raise prices above world levels and therefore about the exact amount of this subsidy, but it clearly exists and is very big. What is clear is that we can make big inroads into the cost imposed on UK consumers by the EU’s external tariff and non-tariff barriers by cutting both kinds of barriers as soon as we leave the EU, which we will be able to do if we leave without a withdrawal agreement. By contrast, under the Chequers plan, we would not be able to reduce any tariffs on non-EU imports until the so-called “Facilitated Customs Arrangement” can be made to work (which seems to be either 2022 if your are really optimistic, or never), and we would be permanently locked in to the EU’s non-tariff barriers against goods imports from non-EU countries.

So what should we do from 30 March 2019, when we have left the EU, to keep goods flowing from the EU27 to the UK, and also to reduce tariffs and NTBs on goods coming in from the rest of the world?

Tariffs on imports after Brexit

After Brexit, the UK will not have to charge any tariffs on anything unless we want to. The depth of ignorance in public discourse about tariffs and tariff policy is probably the result of us having outsourced tariff policy to the EU for the last 40 years. Tariff policy used to be the subject of lively and informed political debate: the trade off between protection of producers and higher prices for consumers was well understood.

(1) Goods that we do not make in the UK

The first point is that absolutely no purpose is served by imposing tariffs on goods which are not made or grown in the UK. A tariff by definition is a discriminatory tax whose purpose is to increase the cost of imported goods in order to benefit domestically produced goods which do not bear the tariff. By contrast, an excise duty (such as the duties on tobacco and alcoholic drinks) bears equally on imported and domestic goods.

If there is no domestic production of a particular kind of good, then a tariff has just the same effect as an excise duty. We don’t levy excise duties on fruits or other foodstuffs, so why on earth should we levy a 16% tariff on oranges which has the same effect as an excise duty, and just means that food prices will be higher than they need to be?

Some people suggest that we should keep this kind of tariff in order to “hurt” the EU27 if we leave without a deal. The purpose of our tariff policy should not be to impose damage on the EU economy and exporters for the sake of it, particularly where such steps would also damage consumers in this country. Instead, the objective should be to keep trade flowing as freely as possible and to benefit our own consumers and economy.

And keeping the 16% tariff would not as such hurt the EU27. If we get rid of the tariff, then EU27 orange growers will have to match the world price of oranges from Florida or elsewhere, which will directly benefit our consumers. If we keep the 16% tariff, then we will have to impose it equally on oranges from the rest of the world, so the EU27 will face exactly the same price pressure but we will have wiped out the benefit to our consumers.

This means that we should in general scrap tariffs on products where the UK has little or no domestic production, giving huge benefits and an immediate ‘Brexit dividend’ to lower income families.

(2) Goods where there is significant UK production

So what should we do where there are high existing EU tariffs and where there is a significant UK industry?

Let us take, for example, beef, which the Sunday Times story singled out as being at risk of being subject to 40% tariffs if the UK were to apply the EU’s current external tariff to imports from the EU27.

The answer is to apply a UK tariff to beef imports from both the EU27 and the rest of the world, but to set it at a lower-than-EU-tariff level which maintains the price of beef in the UK domestic market and does not increase it. Beef farmers in the UK have a legitimate interest in not suddenly being subject to a sharp price fall which could happen if tariffs were to be scrapped overnight; but equally consumers have a legitimate interest in not having prices go up.

In the longer term, we could move back towards the pre-1973 system of agricultural support, under which if we want to subsidise farming it should be done via direct payments and not via artificially inflating the price of food to consumers. See Warwick Lightfoot “The Common Agricultural Policy is emblematic of all that is wrong with the EU”.

(3) Components and intermediate goods

It has been argued that some industries with highly integrated supply chains would be hit hard if tariffs were imposed between us and the EU. If we leave on WTO terms we cannot stop the EU imposing tariffs on inward moving goods — indeed, under WTO rules the EU would be obliged to levy whatever is its standard external tariff is on imports from the UK.

But it does not follow that the UK is obliged to or should levy tariffs on goods going in the opposite direction. For example, in the car industry the UK could zeroize tariffs on car components. As required by WTO rules, the tariffs would be made zero on components from the EU and also at the same time on components from the rest of the world.

Although the UK cannot prevent the EU from imposing its current 10% external tariff on cars imported from the UK into the EU27, we can prevent car manufacturers having to pay unnecessary import tariffs on components imported into the UK and assembled into a car here. Where existing supply chains involve acquiring components or sub-assemblies (such a gearboxes or engines) from within the EU27, a zero tariff policy on imports of components into the UK would avoid hitting car manufacturers with UK import tariffs on components sourced from the EU, and also allow them to source components from the rest of the world more cheaply than at present.

Far from damaging the car industry in the UK, such a scenario would boost its competitiveness.

But does the UK car components industry need to keep the tariffs on components to protect itself? The answer is “no”. The pound’s exchange rate fluctuation since the Referendum has already benefited UK based manufacturers by more than the few percentage points of the EU tariffs on car components. These tariff rates on components are a lot lower than the 10% tariff on finished vehicles.

(4) Sweep away pointless tariffs

More generally, we should scrap existing low level tariffs on all kinds of goods. Collecting tariffs involves costs on the part of the government and on the part of businesses in declaring, administering and paying them. It is hard to see what is the purpose of tariffs which are below 5% or so, when foreign currency movements of greater than that frequently occur.

Getting rid of low level tariffs on a wide range of goods will reduce the administrative burden on customs of having to cope with imports from the EU27 on top of imports from the rest of the world.

Tariffs on UK exports to the EU27

One consequence of leaving the EU without a trade agreement is that the EU will be entitled – indeed obliged under the MFN principle – to charge its standard tariffs on imports of goods from the UK into the EU27. While the UK can control and therefore reduce the level of tariffs on imports from the EU27, we cannot prevent the EU from charging its standard tariffs on goods flowing in the opposite direction. WTO members are not allowed to discriminate in the level of tariffs they charge, so UK exporters cannot be penalised by the EU compared with exporters from other countries.

However, these MFN tariffs under the EU’s Common External Tariff (CET) have been calculated in a study by Civitas and they would amount to about £5.2bn per year. (That figure is based on 2015 trade volumes but will not be greatly different by 2019). This cost would be borne partly by UK exporters and partly by consumers in the countries of importation, depending on competitive forces in the markets concerned.

To put that figure in perspective, it is less than half the current net contribution which the UK pays into the EU budget each year. By leaving without a deal we will avoid having to pay £37bn to the EU which we do not owe, so releasing money which could be used to reduce the impact of those EU tariffs on affected industries. In fact, it is against WTO rules to pay money directly to exporters to cover tariffs or other export costs, but the money could be used for wider ranging tax cuts on industries adversely affected.

This figure is in fact remarkably low, at £5.3bn on UK goods exports into the EU (in 2015) of £117bn, or under 4.5% on average. This reflects the fact that the UK’s exports into the EU27 are mainly in low tariff areas which receive comparatively little protection against imports from the rest of the world, by contrast with the EU27’s goods exports into the UK which are concentrated in higher tariff sectors.

In an ideal world a free trade agreement with the EU would obviate the need for UK exporters to face these tariffs, but the maximum cost of EU tariffs is frankly trivial compared with the huge benefits of not paying the ‘divorce fee’ to the EU, and more importantly the huge ongoing costs which would flow from a Chequers type deal or any deal which restricts the UK’s ability to reform its laws in the areas of employment, environment or technology.

Non-tariff barriers on imports from the EU

Much of the hysteria about ‘shortages’ of goods such as food and medicine seems to be based on the idea that the UK would impose non-tariff barriers against the importation of goods from the EU27. Not only would such an action be criminal stupidity, but it would require a positive amendment to the law to achieve it.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 ‘repatriates’ into UK law the corpus of existing EU laws. This includes laws which provide for example that it is lawful to import into and sell in the UK medicines made in a factory in Germany under the supervision of the German authorities. So there will be no legal barrier against the continued importation into the UK after 29 March 2019 of goods made and certified under EU standards and rules.

So claims that there will be shortages are completely baseless.

But we can and should go further. EU law has been effective in reducing NTBs on goods flowing between EU member states. By contrast, EU law as interpreted by the ECJ has been positively hostile to the flow of goods from non-EU states and has forced Member States to impose barriers even where they do not want to.

This problem can and should be corrected after Brexit. The effect of the Withdrawal Act is that Articles 34-36 of the TFEU (formerly the Treaty of Rome) on free movement of goods will continue to have effect after Brexit as part of EU law. These Articles contain general rules against imposing restrictions against the import of goods from other EU member states unless they are objectively justified.

It would illogical to continue such rules as part of our law after Brexit if we have no trade deal with the EU, since it would discriminate in favour of the EU and against other countries without any objective justification. But the correct way to rectify this deficiency is not to abolish these rules (which are beneficial in opening up markets), but instead to extend them to cover imports from all states inside the EU and outside. There is power to do this by statutory instrument under section 8 of the Withdrawal Act in order to rectify the ‘deficiency’ that would exist in retained EU law if these rules were to apply illogically only to the EU member states after exit.

(1) NTBs – product licences

Another important but little understood feature of the EU Single Market is the regulatory restrictions which Single Market rules impose upon Member States against trade with non-EU states. An example is an ECJ case about licensing of agrochemicals (Case C-100/96 R v. MAFF ex p British Agrochemicals Association [1999] ECR I-1499), where the ECJ ruled that it was contrary to Community law for the UK Ministry of Agriculture to grant licences to products from non-EU countries which were identical to, and from the same source as, agrochemicals licensed here. The UK as a result was compelled to ban the import of these products from a non-EU country because they had not gone through the EU-mandated regulatory system even though there was actually no objective reason at all for excluding them.

This kind of restriction is completely pointless and indeed damaging to consumers in the UK – in the above case, the consumers of the products were UK farmers who were deprived of the chance of buying identical pesticides at lower cost from non-EU countries.

Under the powers granted under section 8 of the Withdrawal Act, we should correct retained EU laws which only permit products to be imported which have been licensed in other EU member states, and instead permit products to be imported from the rest of the world and licensed here in all cases where there is no objective reason not to license them here. For example, if a new drug is assessed by the US FDA as being safe and efficacious, the UK’s own drug licensing authority (the MHRA) should be empowered to recognise that assessment here and let the drug onto the market in the same way as drugs licensed by the European Medicines Agency. This is what Swiss medicines law – a country with a huge drugs industry – permits.

At present the UK’s MHRA operates in parallel with the EMA, and the EMA has the sole right to license drugs in certain specialised areas. Given the strength of our science in this field, it is well within our scope and capability for the MHRA to resume responsibility for licensing drugs in the UK across all sectors, although it would be sensible to maintain automatic recognition of EMA licences for an interim period. Building up the MHRA to be a fully capable world-class regulator in this field, whose assessments would command recognition in other countries, would be a source of influence and revenue and would further boost the UK’s already strong pharmaceutical industry.

(2) NTBs – intellectual property

The ‘Fortress Europe’ mentality also applies in the field of intellectual property, where the ECJ has ruled that trade mark rights can be used by trade mark owners to exclude their own genuine goods from the EU market. One leading example concerned Tesco, which bought Levi jeans in North America more cheaply than in the UK, imported them to the UK but was then subject to an ECJ ruling which prevented the jeans being sold here under EU intellectual property rules. The ECJ ruled that Levi Strauss could use its trade mark rights to prevent the importation and sale of its genuine jeans, because it had not consented to the placing of these particular consignments of jeans on the market within the EU (Case C-415/99 Levi Strauss & Co v Tesco Stores).

Trade mark owners of course are entitled to take action against goods on which someone else has used their trade mark. But trade mark rights do not give trade mark owners the right to interfere with or control the sale by other traders of their own genuine goods on the market, save in exceptional circumstances where the sale damages the reputation of the mark. So in the past UK courts have rebuffed attempts by trade mark owners to use trade mark rights to maintain higher prices in the UK by preventing their own genuine goods from being imported into the UK from markets where they are sold more cheaply.

In a case called Revlon v Cripps & Lee [1980] FSR 85, the Court of Appeal rejected an attempt by Revlon to stop a third party trader who was importing genuine Revlon cosmetics into the UK from the USA, where Revlon had put them on the market at lower prices than in the UK. The goods were genuine goods put on the market by the trade mark owner and under English law it did not matter that they had been put on the market elsewhere in the world rather than in the UK.

Under EU law, the ECJ has developed a similar rule under which a trade mark owner who puts goods on the market in one Member State cannot use trade mark rights to prevent those genuine goods circulating into other Member States and being sold there. But there is a big difference from the previous English law approach. Under the ECJ’s case law, this principle only applies to goods placed on the market inside the EU internal market and not to goods put on the market by the trade mark owner in the rest of the world.

And the ECJ has gone further. Under harmonised EU trade mark law introduced by the 1989 Trade Marks Directive, the ECJ has ruled in a series of cases (of which Levi Strauss v Tesco is one) that if the trade mark owner objects, the courts of Member States must prohibit the importation into the EU of genuine trade marked goods put on the market by the trade mark owner outside the EU.

This has had profound and far reaching effects, since it allows brand owners of a wide range of branded goods to maintain higher price levels inside the EU than on other world markets, and then to use their trade mark rights to prevent so-called “parallel importation” of the cheaper genuine goods into the UK or other parts of the EU. Many major brand owners expend very considerable efforts in suppressing the so-called parallel trade in order to keep up their price levels inside the EU.

Interestingly, this problem was the subject of a wide-ranging House of Commons Select Committee investigation and Report as long ago as 1999, whose Conclusion was that maintaining this exclusion of non-EU goods for all sectors was unjustified in view of the consumer benefits which would come from permitting importation from outside the EU. They recommended that the UK government should work with the EU Commission to try to bring about this change, but obviously nothing has been or can be done while we are still inside the EU and subject to the jurisdiction of the ECJ.

When we leave the EU on 30 March 2019, the picture will change. At present, section 12 of the Trade Marks Act 1994, which reflects the EU’s Trade Mark Directive, reads:

12 Exhaustion of rights conferred by registered trade mark.

(1) A registered trade mark is not infringed by the use of the trade mark in relation to goods which have been put on the market in the European Economic Area under that trade mark by the proprietor or with his consent.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply where there exist legitimate reasons for the proprietor to oppose further dealings in the goods (in particular, where the condition of the goods has been changed or impaired after they have been put on the market).

It would clearly be illogical to keep this section in its present form after we have left the EU, because it discriminates between goods placed in the market inside the EU or elsewhere in the EEA, and goods placed on the market in other countries. So it must be changed.

It would be theoretically possible to change it so it just refers to goods placed on the market inside the UK. But this would make the present situation even worse, since the UK market would be isolated even more than at present, and UK consumers would be even more vulnerable to being overcharged by multinational brand owners.

So the right course is to change it so it refers to goods placed on the market by the trade mark owner anywhere in the world – so-called “global exhaustion of rights”. Interestingly, both Singapore and Hong Kong chose to copy out into their laws many provisions from the UK’s Trade Marks Act 1994, but both jurisdictions chose to alter the UK Act’s section 12 in order to provide for global exhaustion of rights. Section 29(1) of Singapore’s Trade Marks Act reads:

29.-(1) Notwithstanding section 27, a registered trade mark is not infringed by the use of the trade mark in relation to goods which have been put on the market, whether in Singapore or outside Singapore, under that trade mark by the proprietor of the registered trade mark or with his express or implied consent … (emphasis added)

Section 8 of the Withdrawal Act allows anomalies such as section 12 of the 1994 Act to be corrected by statutory instrument. Here, the clear choice should be to follow Singapore and Hong Kong in amending section 12(1) to cover goods placed on the market anywhere inside or outside the UK with the consent of the trade mark owner.

There are also very similar provisions in other legislation relating to registered designs and copyrights, and more recently to certain patents. These also should be amended to provide for global exhaustion. These changes will demolish the significant EU-imposed barriers which currently result in UK consumers being held captive inside a high-price zone and produce major economic benefits.

Non-tariff barriers on imports from the UK to the EU

Obviously, the rules which the EU applies to imports from the UK are not under our control in the same way as the rules governing imports from the EU27 into the UK. This has led to suggestions that the EU27 will simply refuse to recognise any UK goods as conforming with their required product standards despite the fact that unless and until the UK chooses to change its rules and standards, goods made here will in fact continue to comply with EU rules.

This however is to disregard two constraints on the EU. The first is the WTO Agreements, principally the WTO’s Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), and Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS), Agreements. These require WTO members to recognise that goods and agricultural produce from other WTO members are compliant with the standards which they impose on domestic goods, unless there is an objective reason for refusing them entry or for not recognising e.g testing certificates issued in another state.

Where the UK continues to follow EU rules after exit, no such objective reason will exist, unless and until the UK decides to change those rules in particular sectors. The EU would therefore be on to a hiding to nothing in the WTO disputes procedure if it were arbitrarily to restrict imports of goods from the UK after Brexit.

The second reason relates to the EU’s own legal order, under which international agreements concluded by the EU, including the WTO Agreements, form an integral part of the EU’s legal order. While the ECJ has been resistant to the concept that the WTO Agreements as such have direct effect in EU law, they are relevant to the interpretation of provisions of EU law which are intended to give effect to WTO obligations.

In almost all areas, the EU has existing powers to recognise both the standards and the “competent authorities” (relevant regulatory authorities) of non-Member countries as complying with the standards necessary for importation of the goods concerned into the EU. These have been adopted into EU law in order that the EU can comply with its obligations under the SPS and TBT Agreements.

In general, such powers of recognition are delegated to the EU Commission, which can enact the necessary regulations itself without the need for legislation to go through the Council of Ministers or the European Parliament. One of many examples of how this system works can be seen in Commission Regulation (EC) No 798/2008 of 8 August 2008 “laying down a list of third countries, territories, zones or compartments from which poultry and poultry products may be imported into and transit through the Community and the veterinary certification requirements.”

This is typical of the many hundreds or thousands of instances in which the Commision has delegated powers to make formal regulations which recognise imported goods as satisfying EU standards. Not only does the Commission possess the necessary powers to recognise UK goods as conforming to EU standards after Brexit, but it would lay itself open to legal challenge by companies whose business would be adversely affected if it were to fail to do so.

Quite apart from these legal constraints, the EU has a strong self-interest in permitting the continued importation of objectively compliant UK goods into the EU. For example, if the EU were suddenly to refuse to recognise medicines manufactured in the UK as compatible with EU law it could lead to serious consequences and even the death of patients who need the medicines.

Although this is an extreme example, consumers and industry within the EU would be damaged if if the Commission were to fail to exercise its powers to recognise UK goods as conforming to EU standards.

For these reasons, Armageddon type predictions that the EU would freeze out UK goods by refusing to recognise them as complying with EU standards in breach of WTO rules and in a worse way than it treats any other non-EU country are simply not realistic.

Trade agreements with non-EU countries

All the above measures can be taken to reduce costs to UK consumers and businesses by removing barriers to importation from the rest of the world without waiting for the UK to conclude trade agreements with anyone. Obviously, trade agreements can produce additional benefits, by reducing barriers to exports into free trade partners and by further reducing import barriers by tariff elimination and agreeing mutual recognition of regulatory standards.

But in the debate about Brexit and international trade policy, it often seems to be assumed that the benefits of an independent UK trade policy only come when we conclude trade agreements. This is just not true, since all the measures outlined above to gain the benefits of reduced barriers to imports can be reaped by unilateral action and immediately on 30 March 2019. (People sometimes argue that we should keep harmful tariffs on imports in order to “trade them away” in talks on trade agreements. This is a complete misconception – the UK will have plenty to offer prospective free trade partners in market liberalising without needing to retain self-harming tariffs and NTBs just to be used as bargaining counters.)

Conclusions

The positive advantages of leaving the EU without a trade agreement and without a withdrawal or transition agreement are enormous. Given the Prime Minister’s strange decision to abandon of any attempt to negotiate a free trade agreement with the EU, it is the only way forward which fulfills the decision of the British people to leave the European Union. It hands back control and it leads to huge economic benefits.